Lake Okeechobee discharges to the St. Lucie River will end Saturday and be reduced to the Caloosahatchee River, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers announced Friday.

The reason for that decision is lack of rainfall and a quickly receding lake — not traces of low-toxic algae seen at the Port Mayaca and St. Lucie floodgates last week, according to Col. Andrew Kelly, the Corp’s Florida commander.

“The short answer is no,” Kelly said when TCPalm asked whether algae was a factor in the Corps’ decision. “It was not about algae, it was all about lake recession.”

Having receded about a foot since discharges began 34 days ago, the lake’s level was about 14 feet, 2 inches Friday. That still isn’t as low as the Corps typically wants it to be to make room for heavy summer rains — historically 12½ feet by June 1.

The Corps previously has acknowledged it might have to settle for 13½ feet.

The average rainfall in March was 1.6 inches less than usual, according to John Mitnik, the South Florida Water Management District’s chief engineer.

“The lake is receding in the dry season, nature has taken over,” Kelly said Friday, adding that normal lake operations will resume from the “deviation” that allowed discharges now, in the hope of curbing releases containing harmful algae blooms this summer.

Algae visible on Lake O

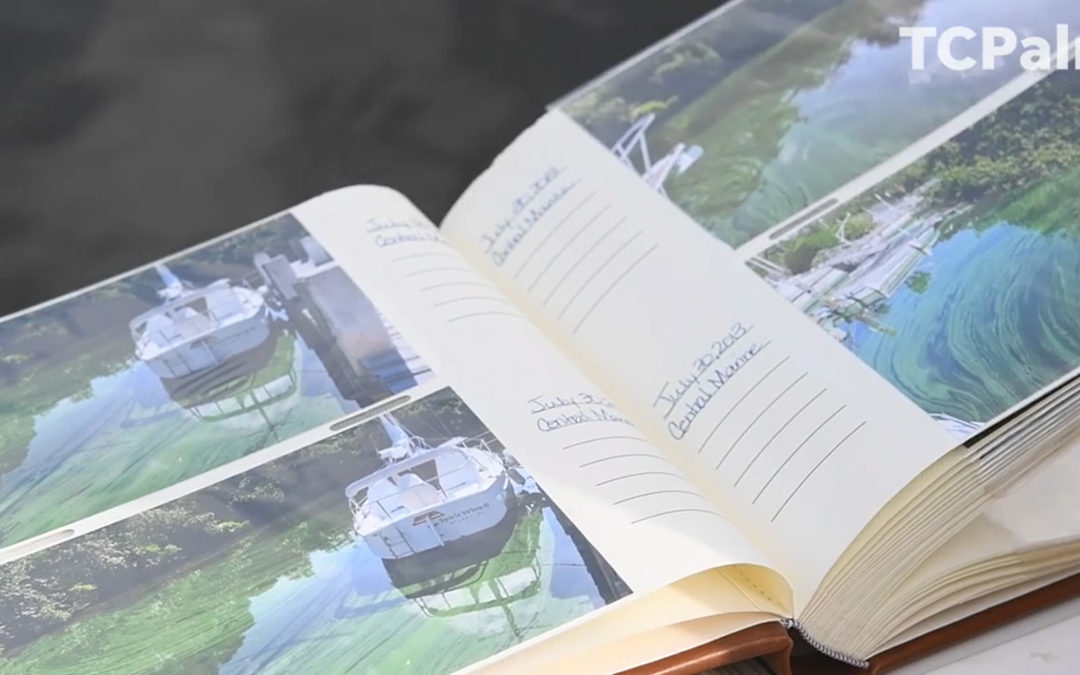

A “widespread” bloom of cyanobacteria, commonly called “blue-green algae,” coated Lake O’s western coastline near Clewiston Wednesday, according to aerial photographs the Calusa Waterkeeper shared on social media.

A blue-green algae bloom was also photographed Friday near the entrance of the Port Mayaca lock, according to Indian Riverkeeper Mike Conner.

“Lake Okeechobee cyanobacteria bloom is underway, now both sides of the lake,” Conner posted to Facebook Friday afternoon.

There was also a visible bloom upstream of the Moore Haven Lock, according to Calusa Waterkeeper, a Fort Myers-based environmental nonprofit.

There were 22 water samples collected by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection between April 2 and Thursday. “Algal bloom conditions” were observed at 14 of the sites, according to the agency’s weekly blue-green algae update.

Traces of algae were seen March 29 at the Port Mayaca Lock, which releases lake water east to the St. Lucie River and west to the Caloosahatchee River, as well as the St. Lucie Lock, which releases water to the St. Lucie River.

The algae contained microcystin, a toxin that measure 0.79 parts per billion at Port Mayaca, according to Martin County officials, and 0.34 parts per billion at the St. Lucie Lock, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Water containing 8 parts per billion or more is considered too hazardous to touch, ingest or inhale, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Though the algae’s toxicity was considered low, it prompted an avoid-water advisory from the DOH-Martin office. Warning signs were posted at the Phipps Park boat ramp and St. Lucie Lock entrance April 2, said Nick Clifton, DOH environmental manager.

How much water has been released?

Since discharges began March 6, nearly 10 billion gallons of polluted freshwater has passed through the St. Lucie floodgates into the brackish St. Lucie River, Corps data showed through Tuesday.

Discharges to the Caloosahatchee will be reduced to a weekly average rate of 646 million gallons per day from 775 million gallons per day. On April 3, the Corps reduced discharges to both coastal estuaries:

- St. Lucie: To 193 million gallons per day from 323 million gallons per day

- Caloosahatchee: To 775 million gallons per day from 969 million gallons a day.

The discharge event prompted Treasure Coast lawmakers this week to pressure the Corps to stop.

U.S. Rep. Brian Mast, R-Palm City, wrote the agency a letter Monday, cosigned by Florida Sen. Gayle Harrell and Florida Rep. Toby Overdorf, both of Stuart.

They urged the Corps to prohibit discharges to the St. Lucie River and make it a policy to send excess lake water elsewhere. It’s a move the agency’s own modeling shows is possible.

The Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual, which the Army Corps is currently in the process of rewriting for the first time since 2008, is nicknamed LOSOM.

“We write to urge you to seize the once-in-a-decade opportunity provided by the drafting of (LOSOM) to stop poisoning our community,” the letter reads.

Mast followed up with a second letter Wednesday, raising alarms about the estuary’s ecological health.

“These releases are already having an impact on the health of the fragile ecosystem in the St. Lucie,” Mast wrote to Kelly. “While I understand the Army Corps’ goal is to make preventative discharges now in an effort to avoid discharges during the summer, continuing these releases indefinitely … will put lives at risk.”

Is 4 inches worth the risk?

If the Corps had continued to discharge lake water into coastal estuaries at its most recent rate, that would’ve contributed to a lake level reduction of about ⅓ of a foot through June 1, according to TCPalm’s calculations, which didn’t factor in unknown variables such as rain, evaporation and farmers siphoning lake water for irrigation.

That amount — roughly 4 inches — left some environmentalists wondering whether continued damage to the St. Lucie River now outweighed the hope of curbing discharges this summer, when algae blooms typically are bigger and more toxic.

“It’s the duration that hurts,” sometimes more than the volume, said Mark Perry, executive director of the Florida Oceanographic Society in Stuart.

Even a small amount of discharges can damage the river if they continue for several months, he said.

“It’s not really significant enough perhaps to continue to damage the estuaries with these discharges.”

One of the best measures of the St. Lucie estuary’s health is oysters, whose spawning season is peaking from now through May, Perry said. The animals thrive in brackish water, but can die after being inundated by the lake’s freshwater for too long — typically 28 days for adults and 14 days for juveniles, Perry said.

Salinity levels are declining slowly, but at the current 15 parts per thousand, they remained in the “good” range for oyster health Thursday, according to Lawrence Glenn, director of the SFWMD’s water resources division.

Lake O water is “impacting the estuary’s salinity and damaging oyster beds, which as you know, is a key indicator that the health of the estuary is declining,” Mast wrote to Kelly Wednesday.

For more news, follow Max Chesnes on Twitter.

Max Chesnes is a TCPalm environment reporter covering issues facing the Indian River Lagoon, St. Lucie River and Lake Okeechobee. You can keep up with Max on Twitter @MaxChesnes, email him at max.chesnes@tcpalm.com and give him a call at 772-978-2224.