How toxic are cyanobacteria?

With the Department of Environmental Protection conducting more routine water tests than ever before, health department and water management officials are also more aware than ever of where cyanotoxins are occurring.

Blue-green algae, which is actually a single-cell cyanobacterium, is everywhere in freshwater systems, but isn’t always toxic. It’s also fleeting, so there may be toxins one day that are gone a few days later.

But unlike Florida’s Healthy Beaches program, which has warned for more than two decades when ocean waters test positive for enterococcus — fecal contamination — rules for toxic cyanobacteria from blue-green algae are not as resolute.

The Healthy Beaches program is part of a federal project administered by the Environmental Protection Agency. The U.S. Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health Act, or BEACH Act, provides grants to monitor the presence of pollution from E. coli and enterococci bacteria at more than 3,500 beaches along the nation’s coastline and Great Lakes.

When a beach tests above a certain threshold, the Department of Health in Palm Beach County issues a written health advisory about the poor quality water. Another notice is issued when the advisory is lifted.

The state’s Blue-Green Algae Task Force discussed the lack of regulation and statute on how and when to notify people of a toxic cyanobacteria contamination last summer. The task force was created by Gov. Ron DeSantis soon after he took office in 2019.

“It’s been almost two years since the devastating 2018 cyanobacteria crisis that coincided with one of the worst red tide blooms in state history and yet we still don’t have adequate public advisories of the risk of blooms,” said Friends of the Everglades Executive Director Eve Samples during a July 29 task force meeting.

Matanzas Riverkeeper Jen Lomberk told the task force that of 31 water access points visited by waterkeepers statewide last summer, all had cyanobacteria blooms, but just nine had warning signs.

“Despite whatever health rules exist on paper, they are not being implemented on the ground,” she said at the July meeting.

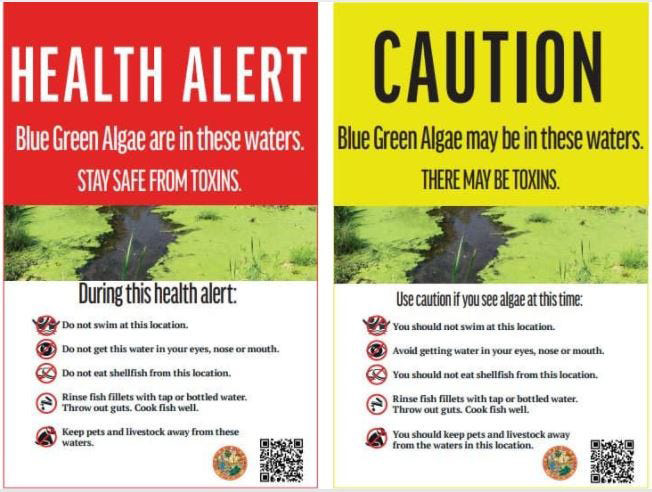

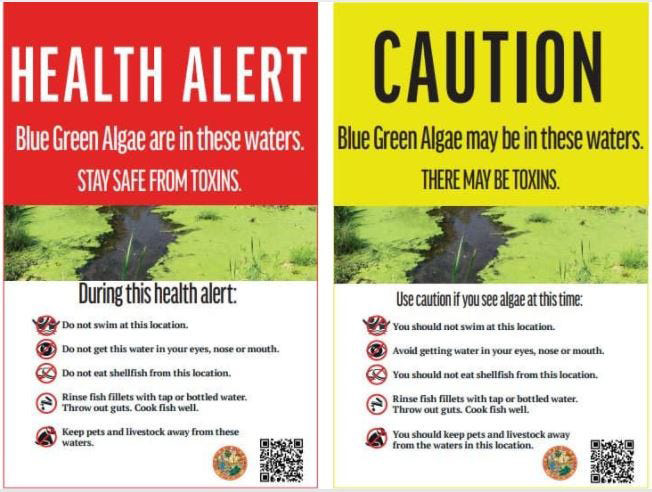

The process to alert the public about a toxic blue-green algae bloom includes the DEP testing the water, which can take two to four days, and posting the information on its public website. From there, the Department of Health reviews the data and decides whether to issue an advisory and what kind of sign to put out.

Kendra Goff, a state toxicologist with the Florida DOH, said at the July meeting that COVID-19 had taken attention away from working on how to better communicate harmful algae blooms.

“Please keep that in mind,” she said. “The COVID-19 response has been all-encompassing throughout the department of health.”

Are algae warning signs and health alerts the same thing?

The signage has become more consistent in Palm Beach County.

When a March 15 water sample near Spillway Park where the C-51 empties into the Lake Worth Lagoon tested positive for toxins, the Florida DOH sent an email to the health department in Palm Beach County. The note said that the state had given out signs “should you and local stakeholders want to post information when toxins have been detected in areas where people and/or pets can contact the bloom.”

The March 15 test found only a trace of microcystin — less than 1 ppb — but signs were posted at Spillway Park. No formal written health alert was issued.

“Any level of toxin is potentially not good for you,” said James Sullivan, executive director of Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute and an algae task force member. “That’s why they call it a toxin.”

Last month, samples taken between May 6 and May 20 had tested positive for toxins ranging from 0.42 ppb near Spillway Park to a May 13 reading of 86 ppb near Southern Boulevard and State Road 7. The 86 ppb — more than 10 times higher than what the EPA considers harmful to humans for recreational use — triggered the closure of a critical flood control structure on the C-51 Canal so waterways downstream would be shielded.

But no formal health alert was issued.

“You probably didn’t see health alerts before because they weren’t doing them consistently,” Sullivan said. “How you communicate to the community at large is a bigger problem than what most people consider.”

There was a health alert issued in April when the water at the Pahokee Marina tested 100 times higher than what is considered harmful. There was also one issued May 28 when West Palm Beach’s water supply was infected with the cyanobacteria toxin cylindrospermopsin at levels that were harmful to vulnerable populations.

The health alerts issued this month were non-drinking water sources and ranged in toxicity levels from 0.30 ppb near the center of Lake Okeechobee to 16 ppb near Spillway Park. Signs have been posted at the park since March, but Lake Worth Waterkeeper Reinaldo Diaz said they could be sturdier.

“In Martin County, they have a sheet of aluminum, which is arguably better than here in Palm Beach County where we get a piece of paper stapled to a wood post,” Diaz said. “Without a state law, we are giving the opportunity to settle with mediocrity.”

Sullivan said he hadn’t thought about people not being able to see warning signs from a boat, and that putting them on buoys or bridges would be a good idea. Also, some areas that frequently test positive, or have many recreational users may need permanent signs — something equivalent to alligator warning signs.

The Blue-Green Algae Task force is meeting at the South Florida Water Management District in West Palm Beach on Wednesday beginning at 10 a.m. The meeting is open to the public.

“We are seeing more blue-green algae now and we should expect that until we can turn the tide in our water quality, people need to be alerted to this,” Sullivan said.

Kmiller@pbpost.com

@Kmillerweather