Rodney Barreto, an influential lobbyist who chairs the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, is pressing legal action to let his company fill, dredge and build hundreds of condos and houses on mostly submerged land off Singer Island.

The company, Government Lot 1, LLC, based in Coral Gables, seeks to reopen and expand upon a 1990 circuit court order that gave previous owners the right to fill but not dredge the 19-acre site off Singer Island without requiring permits from state regulators.

Government Lot 1, after buying the site in 2016 for $425,000, proposed three multifamily buildings with 110 units each, 15 single-family lots with two docks each and a 50-slip marina that includes a restaurant and community center on the site. The project called for filling more than 12 submerged acres and dredging another 4, on the northwestern end of the barrier Island, just south of John D. MacArthur Beach State Park.

The South Florida Water Management District in 2018 expressed “serious concerns” about potential impacts on the estuary and determined the plan could not move forward without extensive measures to mitigate environmental damage. The company withdrew its plan but in August 2020 moved to reopen the 31-year-old circuit court case, asserting that its final order should be supplemented to clarify that state regulatory approvals are unnecessary to move ahead with development. The company acknowledges that federal approval, from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, still would be required.

Opponents argue that the site should be preserved, that its clear waters and sea grass serve as a nursery and migratory spot for manatees, endangered green sea turtles and smalltooth sawfish and other abundant wildlife.

Lisa Interlandi, executive director of the Everglades Law Center, called the project a blatant conflict of interest for Barreto and one that compromises his agency’s responsibility to protect Florida environmental treasures. Her organization, which litigates for environmental protection, last week moved to intervene in the case on behalf of nonprofit Lake Worth Waterkeeper, to block the project.

“The days of turning water to land and land to water have thankfully passed,” Interlandi said. “We hope.”

Barreto said the project posed no conflict with his FFWCC duties. The state sold and conferred the right to develop the submerged land decades ago, just as much of the lagoon is developed, he said in an email last Wednesday to The Palm Beach Post.

“Although I will not be directly participating in any decision by the FFWCC, I am prepared to take appropriate action in response to any unlawful interference with my property rights,” he wrote. “Furthermore, I will continue to exercise the duties of my position with the FFWCC in a manner that vigorously protects the state’s resources without abusing its governmental authority in a manner that fails to seek a balance that shows due respect for vested private property rights.”

James. D. Ryan, the North Palm Beach lawyer who filed the motion to reopen the case, could not be reached. Ryan’s motion also asserts that other property owners in that area similarly should be allowed to build on their submerged land without state approval.

Barreto agreed, saying nearby landowners Fane Lozman and Daniel Taylor, with whom he has collaborated in the matter, have identical rights and should be allowed to move forward and coordinate development of their properties with his.

“This approach would improve the likelihood that the taxpayers do not become saddled with an enormous financial obligation, the owners develop a portion of the property in a manner that allows their financial expectations to be realized and some of the property being dedicated to conservation.” Government Lot 1’s 2018 plan called for a 1,200-foot long line of mangroves to be planted on his site.

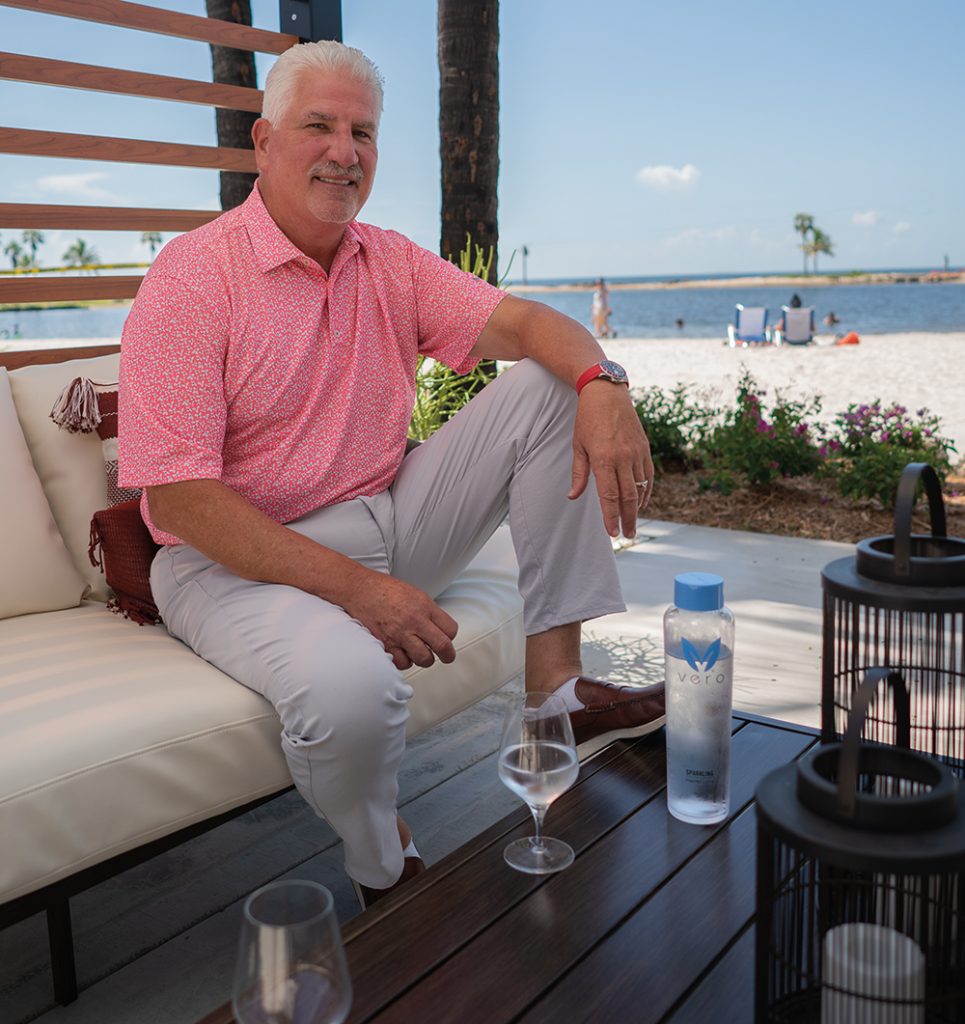

A closer look at Rodney Barreto

Barreto, a lobbyist and one-time Miami policeman, has long been a force in government circles in Miami-Dade County and around the state.

A co-founder of Floridian Partners, a lobbying firm with offices in Tallahassee and Miami, he also presides over The Barreto Group, which specializes in corporate and public affairs consulting, real estate investment and development. He chaired the Super Bowl Host Committee in 2007, 2010 and 2020 and was named to Gov.-elect Ron DeSantis’ Inaugural Committee in 2018.

He was appointed by Gov. Jeb Bush and re-appointed by Gov. Charlie Crist to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, where he served two five-year terms initially, much of that time as chairman. After his terms expired, he became a member of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Foundation, a citizen fundraising and promotional group that supports the commission. Then Gov. DeSantis reappointed him to the FFWCC in 2019.

Reinaldo Diaz, president of Lake Worth Waterkeeper, an environmental monitoring and advocacy group, looked out Thursday over the expanse of mangrove-lined waters rippling above Barreto’s submerged land.

It’s among the most pristine and abundant sections remaining of the lagoon, he said, the water reflecting in his mirrored sunglasses. “You would think somebody in charge of the FFWCC would know the value of a mangrove habitat.”

Blocking it off with seawalls would destroy a sloping shoreline where horseshoe crabs come to nest and a shallow, sea grass lined stretch where bone fish and “extremely rare” smalltooth sawfish swim, he said. What’s more, a decision allowing development here, as it might have been in the past, ignores decades of environmental learning and could have ramifications for habitats elsewhere in Florida, Diaz said. “We know better now.”

One Singer Island resident whose home overlooks Barreto’s site acknowledged that his own property sits on land a developer filled in the late 1950’s. But he agreed with Diaz that society today has a heightened awareness of the need to protect such waters.

A lot of things have changed over the decades, said the resident, who asked not to be named. “Smoking was good for you in 1960.”

Barreto, though, said he has every right to rely on and profit from almost 100 years of political and legislative decisions that shored up the property rights attached to the submerged land he owns.

“Nearly a century ago the governor and his cabinet, acting as the Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund (TIFF) for the state, made a determination that it was in the state’s best interests to sell land in and around Lake Worth (Lagoon) for development,” he said. “In accordance with the General Laws of the State, such sales conferred specific rights enumerated in the law, i.e., to dredge, fill and bulkhead the conveyed land unless the deed expressly included an encumbrance restricting such rights….”

The TIFF sold 311 acres at that time, including the land his company eventually bought, and about half of that total has been filled and sea-walled, he said.

“About 50 years ago, when only a few miles of the lake’s shore remained untouched, the state made a decision to preserve some of it and it did so by purchasing the land that is now John D. MacArthur State Park,” he continued. The state decided not to buy any of the Government Lot 1 land and left the private property rights intact, he said.

Subsequent court decisions confirmed those rights and said the owners could develop the site without permission from any state regulatory agency, he said. “I do not believe the state or the FFWCC has any lawful basis to terminate those rights,” he concluded.

Decision in court’s hands

The court must now decide whether those rights hold against the current of decades of environmental research, regulation and legislation. If they do, it will be left to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to weigh the project on its merits.

“There would likely be discussions regarding the purpose and need of the project, as “housing” is not considered a water-dependent activity,” Army Corps Public Affairs Specialist Nakeir Nobles said Thursday. The project also would have to pass muster with the Endangered Species Act and compensate for environmental damage, she said.

Interlandi said Barreto should deed the submerged land back to the state, as it’s a stone’s throw from MacArthur Park. He has no right to dredge and the state has a responsibility to enforce laws that protect waterways from harmful development, she said.

“Mr. Baretto did not acquire this land 100 years ago, he purchased it approximately four years ago, He has served on the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission for more than 10 years, which is more than enough time to realize that filling in habitat for sea turtles and manatees to build condos and luxury homes would be an extremely bad idea….

“If Mr. Barreto’s approach prevails, what would it mean for commercial and recreational fishing all around the state? How many of these deeds exist in Florida waters and if the state is not able to enforce the law, how much will the public have to pay to protect critical environmental and fishing habitat from development?”

Barreto said he won’t give the property back to the state. If the state wants to conserve it, it can buy him out, he said.

“But we have discussed reaching a compromise that would create permanent protection over some of our land without any expense to the taxpayers,” he said. “This could result in land being added to the park.”

Interlandi dismissed that idea. “In exchange for his being able to develop the land?” she asked. “No way.”

This Thursday and Friday the FFWCC commissioners are scheduled to hold one of their five meetings per year. The Friday session includes a portion for up to three hours of comment from the public on items not on the agenda. Interlandi said she expects members of the public to voice objections to the chairman’s development plans then.