The Lake Okeechobee cyanobacteria bloom has unfortunately been gaining momentum toward bringing us another lost summer.

Since we first reported on the Pahokee Marina there’s been a big focus there. The usual parade of photo ops soon followed, with quite a few attempts to explain the situation thrown in. Many groups incorrectly assumed that the marina is the only place hit with a major bloom right now.

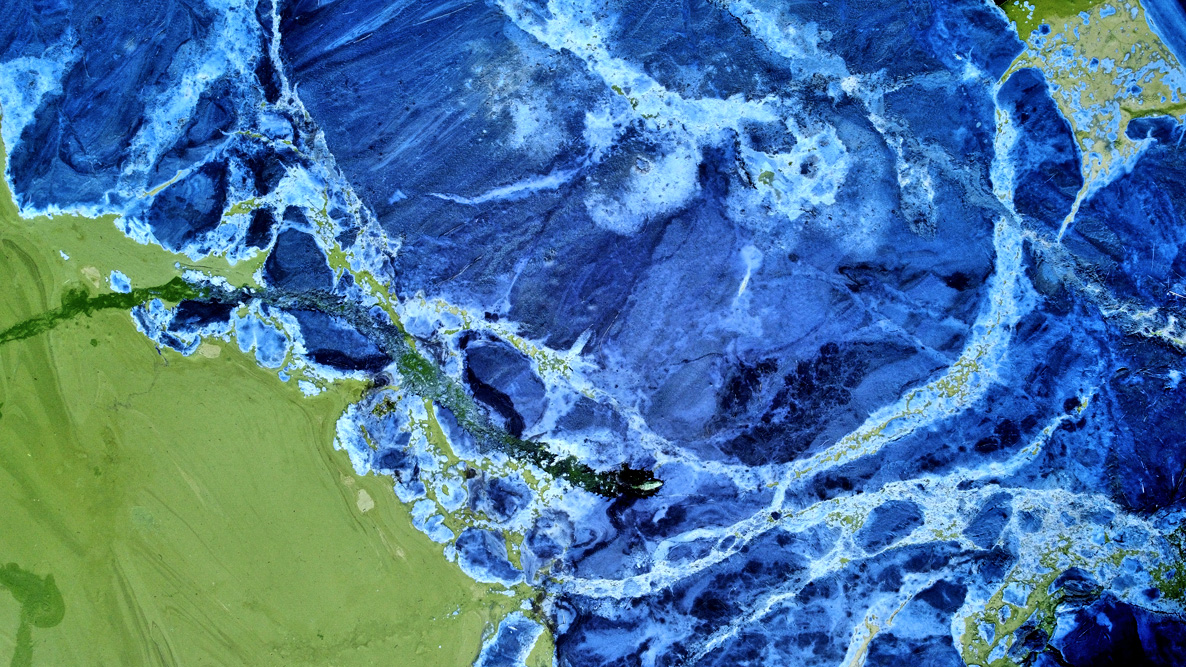

When we first reported the Pahokee Marina bloom we were also quietly monitoring and reporting the total extent of the bloom throughout our watershed. The cyanobacteria bloom goes far beyond the marina, it covers half of Palm Beach County.

Alligator struggling to swim through cyanobacteria bloom in Pahokee Marina, taken April 23, 2021.

First Stop, The Pahokee Marina

Disappointedly even some of the well-intentioned environmental or conservationist groups incorrectly suggested that the Pahokee Marina was a relative newcomer to the cyanobacteria problem. Compared to the other northern estuaries, the Lake Worth Lagoon watershed – specifically throughout the Glades communities – is consistently hit hard on an annual basis often for months at a time. The Pahokee Marina has merely become a canary in the mine. When conditions are ripe for a super bloom in Lake O the marina’s design merely encourages the cyanobacteria to float toward the surface and reproduce into a major bloom there first.

The South Florida Water Management brought a response of vacuuming out the cyanobacteria from inside the marina. A temporary reprieve at best. The conditions throughout the area are still favorable for a super bloom, and it doesn’t look like we’ll have much of a break anytime soon. Serious consideration needs to be made to redesign the walls and docks of the marina to allow better water flow. This wouldn’t solve the cyanobacteria issue of course, but it would help give a little bit of a break to the marina and those that stay there in these early phases of the Lake O super blooms.

Restoring the historic south flow of the Greater Everglades, bringing back habitat to Lake O by keeping its level low, and connecting Lake O to the lower Everglades remains the best answer to fixing the cyanobacteria blooms.

Big Sugar’s PR Campaign of Excuses

The usual cast of Big Sugar defending astroturf groups offered up their own explanation for the bloom here. For example, Scott Martin of Anglers for Lake Okeechobee – a predictable denier of the severity of cyanobacteria blooms – has offered his excuse that the bloom in the marina is the result of the boats pumping out their wastewater into the marina. He even shared a video of how the bloom is “only visible inside the marina walls”, and in his willfully ignorant understanding of science offers that as proof. Reality is, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, the bloom was dispersed throughout the lake (difficult to see on camera but visible in person) and only collects inside in the marina due to the design of the docks and walls that impede water flow there.

Lake O cyanobacteria bloom caught up in the Pahokee Marina in areas where water flow is hindered, taken April 23, 2021.

Martin, Elsken, and others that are part of the Big Sugar paid PR machine have historically claimed all kinds of red herring excuses for the blooms: from septic tanks to overdevelopment, they rely on half-truths to draw the blame from the real culprit of industrial agriculture runoff and industry driven political corruption. All of which should only draw eye rolls were it not for the serious consequences their claims have by distracting the community from the information needed, and by using their influence to seriously hinder Everglades restoration progress.

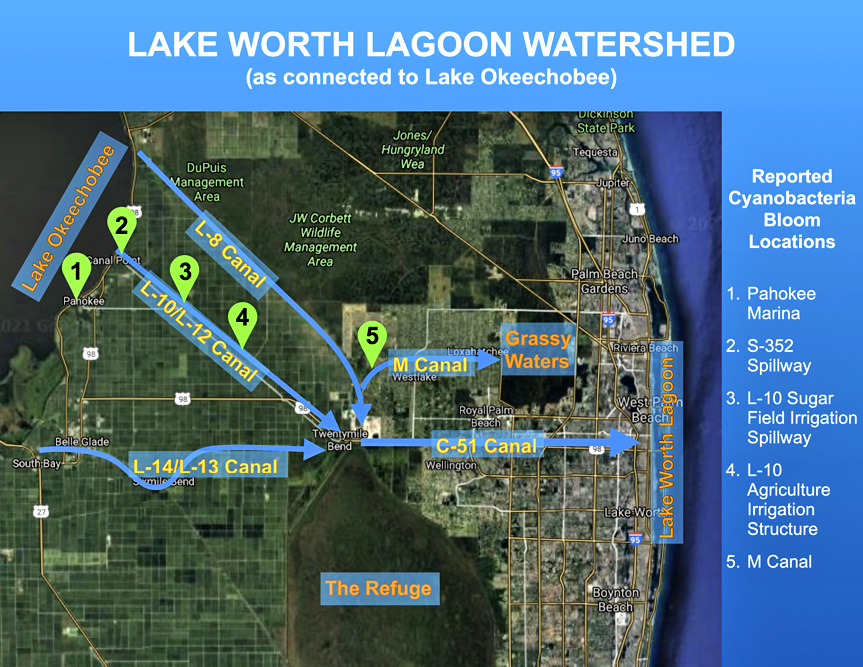

Map of Lake Worth Lagoon watershed with highlighted cyanobacteria bloom areas mentioned in this post.

The Lake Worth Lagoon Watershed

The cause of Lake O’s cyanobacteria blooms comes down to environmental conditions (hot and dry) working with the surplus of legacy nutrient pollution (phosphorus, nitrogen, herbicides and other chemicals) already in the lake, and new nutrient pollution coming into the lake as runoff.

The Lake Worth Lagoon watershed is the clearest example that shows polluted Lake O water as the common denominator for cyanobacteria blooms.

Lake O’s super blooms are easily visible by satellite, that imagery has been crucial to our understanding of how the blooms take over the lake. But the true extent of the bloom outside the lake and throughout our watershed can only be mapped out with fieldwork and an understanding of our watershed and how it works.

The western half of the watershed (west of SR-7/441) consists mostly of less developed agriculture, especially the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) which is dominated by at least half a million acres of massive industrial monoculture farms where sugar is by far the biggest crop. It is in this half where we find the Glades communities. It is this western half of our watershed that is persistently hit hard with cyanobacteria blooms among other serious environmental crises.

Cyanobacteria Throughout Our Watershed

Understanding the agriculture operation of the EAA is the first step to understanding how toxic Lake O water makes its way throughout the Lake Worth Lagoon watershed. The EAA and its historic agriculture operation is the reason behind the need for Everglades restoration. The EAA is the hindrance of waterflow from Lake O to the lower Everglades and eventually Florida Bay.

There’s a need for a massive reservoir that would help move water south. But the real reason behind its need is because the government through the South Florida Water Management District gives too much water for consumption and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection fails to save water from overuse. So now we are forced to use nearly a billion dollars of our taxpayer money for a reservoir project that will likely not be able to fulfill its mission. Big Sugar and their machine prevented an adequate reservoir design by getting in the way of land acquisition and forcing a smaller reservoir design, thereby limiting the amount of Lake O water that would be cleaned. The reservoir is supposed to be for dry season flows, but now as cyanobacteria blooms become more prominent and longstanding, that contaminated water likely will get in the way of the reservoir’s operation. Lake O’s water quality must be addressed, habitat needs to be brought back, but that brings about a massive cost that our government is unwilling to provide. Largely because working on proven fixes to Lake O’s environmental woes would entail calling out Big Sugar as the cause of most of it, and they fund the majority of politicians’ campaigns to make sure that doesn’t happen and to protect their interest in future water rights.

Cyanobacteria bloom in the L-10 Canal, just beyond the S-352 Spillway on Lake O. Here the cyanobacteria is hard to see in the photo because it is dispersed throughout the water column since the water is flowing through here quickly, but cyanobacteria is visible on the rocks along the shore, taken April 26, 2021.

Cyanobacteria bloom in the L-10 Canal, at one of the many structures that sends water for agriculture irrigation, taken April 26, 2021.

Cyanobacteria bloom in the L-10 Canal, at one of the many structures that sends water for agriculture irrigation, taken April 26, 2021.

Cyanobacteria bloom at one of the many structures that sends water for agriculture irrigation off the L-10 canal, sugar fields seen in the background including a recently harvested field with a small fire still going in the background, taken April 26, 2021.

Overhead look at the same structure, cyanobacteria is on both sides of the structure, more so on the upstream side (the right) and on the left cyanobacteria can be seen along the banks of the canal, taken April 26, 2021.

As Lake O water makes its way through the watershed, so does the cyanobacteria.

Another notable – and very concerning – part of the watershed where we reported the bloom is in Loxahatchee at the M Canal. The M Canal is a canal that connects the L-8 Canal (which in itself is connected to Lake O and joins the L-10 at the C-51 Canal) to Grassy Waters Preserve. This is especially concerning because not only is the Preserve and area of critically important habitat, but the Preserve also serves as one of the few surface drinking water sources for our watershed. For some time now we and fellow Waterkeepers have been lobbying to get cyanotoxins onto the Regulated Substance List. No cyanotoxins are listed here, this list would require agencies like municipal water to test for cyanotoxins. So right now, it’s not legally required.

Cyanobacteria bloom in the M Canal in Loxahatchee, the water flows toward the right through a culvert and into Grassy Waters Preserve, taken May 1, 2021.

Just Another Year for the Lake Worth Lagoon

This situation is not unfamiliar to us. Unfortunately for us, the Lake Worth Lagoon is often ignored in discussions of the Northern Estuaries of the Greater Everglades. This is the result of various reasons, one example is the Northern Everglades and Estuary Protection Plan (NEEPP) legislation passed in 2007 that intended to expand the existing Lake Okeechobee Protection Act (LOPA) to the Northern Estuaries of the Everglades. But there’s one glaring problem, NEEPP specifically excludes the Lake Worth Lagoon as a defined northern estuary. This is ridiculous, by all scientific and common sense definitions the Lake Worth Lagoon is a northern estuary of the Greater Everglades Ecosystem so why would law and government not reflect that? Could it be to protect polluter interest?

This glaring omission and other similar policy opens the door for the government to abuse the Lake Worth Lagoon. Our watershed is overlooked in important decision making processes, such as the current changes being made to the Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual (LOSOM) which is coming towards the end of its process. This policy dictates how Lake O water is managed, especially in regards to it being discharged to the northern estuaries. If the LOSOM Project Delivery Team continues their current path we are looking at more polluted Lake O water being sent our way, with even more cyanobacteria blooms to come along with it.

In other words, the cyanobacteria situation is going to get worse for Lake O and the Lake Worth Lagoon. But we do have options, our communities need to take the lead and stand up to this abuse. We can participate in policy changes like LOSOM, where traditionally the other northern estuaries have had adequate but ineffective representation. But we stand a better chance, as explained before, our watershed is the clear example of the real causes to the environmental issues we’re facing. It is our watershed that proves we need real solutions of habitat restoration, a lower Lake O, and a reconnection of that flow of Lake O water to the lower Everglades. We cannot vacuum this problem away and we cannot afford to argue about red herring distractions anymore.

In the meantime: don’t worry about Big Sugar, their fields will be perfectly irrigated using our tax dollars… Might be a good time to move away from the morning sugar in your coffee habit.