I have always found it appalling that anyone would want to ban any book regardless of its content

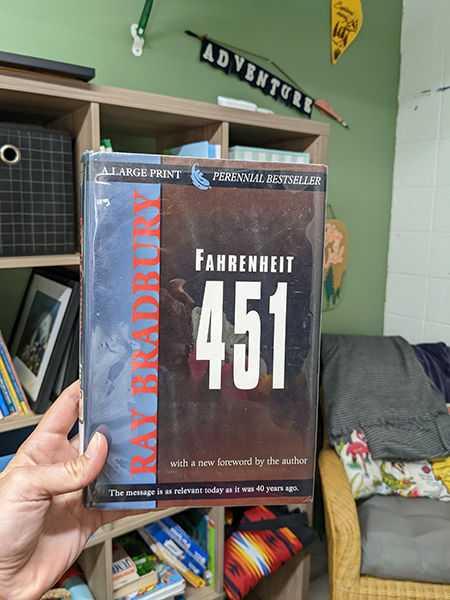

Last week was National Banned Books Week and I have been spending my evenings reading Fahrenheit 451, preparing for Lake Worth Waterkeeper’s first meeting of the Banned Book Club next month. As a book lover and hoarder collector, I have always found it appalling that anyone would want to ban any book regardless of its content as it is a piece of art, an expression of love lovingly written for the consumption of whoever may pass by.

I say this to include all books, fiction, nonfiction, and every other genre of the written word. Think about it, someone had to come up with an idea and have enough courage to write it down and deliver it to the world. Many authors, underappreciated at the time, are now renowned for their literary geniuses.

However written, books are meant to be read and digested. The summation of books represents the full extent of a life well lived. They reflect us, humans, in their words and we devour the ones that speak to us. We reread books with the ferocity of the deprived and they mold us into who we are in the present. They invoke emotion within a single page and we yearn for friendships that end after the back cover closes. So, knowing this why would anyone ever consider banning a book?

The complaint I have heard the most for books being challenged or banned is the potential indoctrination of children. The hypocrisy of this justification is that it is made on the assumption that education in this country is not already indoctrinated. American education is heavily abbreviated and well-edited versions of history always centered around the heroism of the colonist. Our education systems have continuously for generations taken on the perspective of a proud and patriotic country built on the backs of hardworking men. While this may be true and there is much to be proud of, it is not the whole story.

I am reminded of a TedTalk I had watched some years ago given by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The title, “The Danger of the Single Story”. As the title suggests, she discusses her youth in Nigeria and the books she read. She had a vision of what ginger beer was “supposed” to taste like. She came to America for college and her roommate had a vision of what she was “supposed” to be like. She took a trip to Mexico and she found herself appalled at her own preconceived views of what life was like there. She goes on to say, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue but they are incomplete”. The problem with our education is not that it is necessarily untrue, but it is incomplete. The omission of histories paints a somewhat fictionalized version of our American heritage and the banning of books is another form of omission.

I recommend asking yourself, “What is it about this book that makes me uncomfortable?”

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie goes on to talk about power as you cannot discuss stories or narratives without discussing the power of the author, editor, or narrator. “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.” Many books equals many stories. They widen our perspective on what it is to “be” in this world. We meet all kinds of people in stories and we see how we may relate to them. Maybe that is what people are afraid of – having more similarities than differences in those we have blindly hated because we have only been told one story of them. Books build our compassion for the “different” or unusual. They help build compassion for ourselves. Any ban against expanding knowledge and compassion is evidence of the already indoctrinated. This is the hypocrisy of the ban.

If you don’t want a man unhappy politically, don’t give him two sides to a question to worry him; give him one. Better yet, give him none. Let him forget there is such a thing as war. If the government is inefficient, top-heavy, and tax-mad, better it be all those than that people worry over it. Peace, Montag.